V-E day found the men of Company “B”, 86th Chemical Mortar Battalion, in the small town of Hirschau, Germany, which is approximately 30 kms. from the better known town of Amberg. We had been occupying two small villages, and our main duty was to pick up all German soldiers who had donned civilian clothes—soldiers who hoped that they would be passed over in the resulting confusion coincident with the complete Wehrmacht capitulation.

To us, V-E day was just another day away from home, and it brought thoughts of a new theater of war much closer. We heard of gay celebrations and much drinking and making merry by so-called “rear echelon commandos”, but although no mention was made of it, you could feel that most of the men in Baker were thinking of their many buddies who were not with them to share in the peace and quiet that V-E day had brought. Little Mike, Lolly, Mauck, Ollie, and good old Hinch who had been with us all the way through basic and the greater portion of our combat days in Europe, Killer Kane, Campbell (Little Patton the 2nd), Ed Levinson, and many others no longer with us but never forgotten in our thoughts.

Yes—it was an eager bunch of Joes that awaited the good ship “The James A. Farrell” on the 29th of June, 1944. We had come from a most enjoyable and hospitable town named Port Sunlight, about 10 miles outside Liverpool, and now at long last we were headed for France to do battle with the “unconquerable” German, for whom we had been preparing for many long months. We had faith in our particular weapon, a heavy mortar, and there was nothing but praise from all theaters as to the effectiveness of its fire. We were green, yes—but every soldier must have felt as we did. This was it, and if the other Joes could take it we were damned sure we could. We boarded ship in the early evening and after taking our place in the convoy of ships headed for Cherbourg we began our zig-zag course through the sub-infested waters of the English Channel.

Our trip was without excitement until we reached a spot approximately 7 miles from the coast of the Cherbourg peninsula, where the stark realization of the horrors of total war thrust themselves upon us in the form of a mine or torpedo. To this day, the official verdict is still undetermined, whether it was one or the other, but officially or otherwise, something hit us, and we were committed to action before we even knew it. It was this first encounter with disaster that proved the calibre of men we had in Baker Company. Their immediate reactions were more than a commander could have hoped for. In no time at all, officers and men were working like madmen with complete disregard for their own personal safety clearing the rapidly filling hold of men who otherwise would have been trapped and surely drowned in the mass of rubble and debris which had once been materials of war. To try to describe this scene and the actions which took place is humanly impossible, for, to fully appreciate the grim reality of war, one must personally experience the workings of the brain and the weighing of one’s own personal feelings as compared to thoughts that regardless of how much you value your life, there is a job to be done. It should be sufficient to say that our casualties numbered thirty-five, including one man missing, little Mike Babaryka, a favorite with all the men.

For a time it appeared that soon most of us would be swimming in the choppy seas of the English Channel, but fortunately that never happened. An American LST took aboard all survivors of the sinking James A. Farrell. Thus we found ourselves on the way to England, badly in need of equipment and men.

We landed at Portland, England and were taken to The Citadel, a fortress overlooking the harbor. Here we received a fine meal, clean clothes, and the opportunity to shower and shave.

From The Citadel we travelled by truck to Beurnemouth where we worked feverishly to prepare ourselves for another attempt at crossing the channel.

In the unbelievable short time of two weeks, we were again fully equipped and on our way for a second time to join our parent unit which had successfully landed with the same convoy in which we had sailed. This time the trip was without incident except for enemy air activity over Omaha Beach the night we landed. The drone of enemy planes, the steady bark of the ack-ack, the multi-colored tracers that zoomed across the sky like fireworks—all these against a background of the slow, running tide and the bleak Normandy coast with its ghostly ruins impressed upon our minds a vivid picture that was to never leave us. Thus we went ashore, and in very short order, we found ourselves driving over the shell-torn, battle-weary roads of Normandy on our way to the town occupied by our Battalion.

We stayed one day and night with the Battalion, and the next afternoon found us committed to action with the 83rd Division in the vicinity of La Haye du Puits, on the Normandy peninsula. Our very first position was a rather warm one, for after firing our first mission, our area began to receive small-arms and machine gun fire and our platoon leader decided that it was about time for us to start a retrograde movement. All the units which had been in front of us were now barreling down the road past our position going in the wrong direction. We also found it necessary to “partir”, but after the situation again stabilized itself, we returned to our foxholes and then began our long series of attachments, reassignments, and our long journey.

The huge breakthrough at St. Lo will be memorable because of the beautiful sight of thousands of bombers during their saturation bombing of the fixed German defenses in and around St. Lo. As a result, the American tanks could at last stretch out their tracks in the direction of Berlin. We raced down the Normandy peninsula with the infantry trying to overtake the fast fleeing Krauts. At Avaranches we were told that our Battalion had been assigned to the task force which was headed for the impenetrable fortress of BREST!

Our trip across the Brittany peninsula was a glorious one. In every little village and hamlet, the liberated French would shower us with roses, wine, cider, champagne, and apples.

Our first mission on the Peninsula was against the fortress of St. Malo. After placing a murderous fire of White Phosphorus in the installations for a week, the fortress commander capitulated with the remark that: “The enemy will continue to use the deadly White Phosphorus, against which we cannot possibly hold out.” Here, in the handwriting of the fanatical Nazi, Colonel Von Auloch, was visible proof of the effectiveness of our “goon gun.”

After the fall of the Citadel at St. Malo, we were assigned to help reduce the resistance in and around the Brittany town of Dinard, and in very short order, our mission was accomplished, and we were en route again headed for Brest. We were attached to the 8th Division for this particular job, and the brass hats had it all figured out;, whereby General Remcke, the fortress commander would certainly surrender his entire garrison after a three day barrage from artillery, mortars, and fighter bombers. Apparently somebody forgot to tell Remcke what the plan was, for five weeks later we were still battling our way inch by inch against the most stubborn resistance we had yet encountered.

During this engagement, we came in contact with prepared German mine defenses, and the very well known “88s”, along with the very appropriately named “screaming mimies,” shells from a huge trench mortar having a terrific concussion effect. The Krauts used them extensively to cause casualties in areas where troops were well dug in and flying shrapnel could not reach them. The sound of the projectile in flight, resembling the sound of a shearing piece of sheet metal, was not a pleasant one to hear.

We began to feel that Brest would still be holding out long after the Germans on Siegfried Line had surrendered, for it was while we were engaged at Brest that we heard the Siegfried Line had been penetrated and that slow progress was being made into the Reich. We began to feel that we were banging our heads against a stone wall, for the Kraut positions were being taken only after a high cost of life on both sides of the line.

Finally, the complete surrender came, and we had visions of a long rest, perhaps passes to large cities, etc., but that is all they were—just “visions” that never materialized. We rejoined our battalion and after a week of preparations set out on a 600 mile motor march and at the end of the march, we found ourselves under the command of “Old Blood and Guts” Patton, the most bombastic, lovable American general in the ETO. His specialty was tank warfare, and it meant a new kind of warfare for our mortars.

We went into action with the 35th Infantry Division in the vicinity of Nancy, France, and participated in the battle of the Gramercy Forest. In this vicinity the company received an exceptionally severe shelling. It was the very first time that every man in the company from cooks to mortarmen was subjected to artillery barrage. It had been the policy of the company to establish a rear area in a comparatively safe place for the purpose of giving the men on the line a place to rest up for a few days because the company had never been pulled out of the line for a rest period (after an engagement) such as the infantry enjoys. We were committed to combat two days after landing in France, and the Battalion Commander realized the necessity for such a policy, for it would have been humanly impossible to maintain an effective fighting force for such a long period of time if the men were not given the opportunity to rest up and relax after a given number of days on the front lines. The area for such a place was reconnoitered and the entire company was moved into it. The next day the platoons were to occupy gun positions in support of the doughs of the 35th Division. We all considered the area a safe one, and as a result we bedded down for the night without digging holes. At exactly ten o’clock, the first shell came screaming in, and luckily for us, it was short of its mark. It gave us a few seconds to duck into whatever natural cover was available. Evidently the Krauts used the few seconds to make whatever corrections were necessary to get on the target, for the next shell hit directly in the middle of the 3rd Platoon area. For the next twenty minutes, we went through indescribable hell-like tortures. When the shelling subsided, we counted two dead and 17 wounded, vehicles damaged beyond repair, and the mental attitude of the entire company at its lowest ebb since we had been in combat.

We moved from the area immediately and occupied an alternate rest area, and it was here that the company commander made the wise decision of wasting no time in getting the remnants of the company together and going into the line the very next morning in support of the Infantry Division of our attachment. Again the company displayed its recuperative powers, for, this “incident” also was overshadowed by the knowledge that we still had a job to do and a bigger score to settle, for one of the boys who had been killed was Bob Boyington, a nice kid from Louisiana.We began to get hardened to the tribulations of war, and we all had a more grim perspective of what we were up against.

It was during this campaign that we fired numerous smoke screens for advancing infantry, and on several occasions, we worked hand in hand with division artillery using the well known Cub liaison planes as observers for our firing.

The weather conditions were far from favorable. It was the time of the year for rain, mud and more rain. The mud made tough going for the tankers and a small knowledge of our particular weapon is all that is needed to appreciate the work that the boys did on the guns in order to keep them firing. Mortars were fired without locking forks, standards, covered with three foot of mud, and on one occasion one particular mortar “rode” back at least fifteen feet from where the squad leader had first laid it in. Yet, under these trying conditions the men were fully aware of how important it was to maintain the devastating fire the mortars were laying down around the Kraut’s ears and, they all performed miracles, successfully completing every mission assigned to them by the infantry commander.

At that time, the First Army was occupying the headlines, for its progress was increasingly speeding up, whereas the thrust by the Third Army, sorely in need of supplies and materials as a result of its lightning like dash across France and the resulting lengthening of supply lines, was slowly being arrested.

We fought with the Third Army up until October, when word came that we had been assigned to the First Army, and once again we prepared for a long motor march to join the First Army, which at that time was inside the Siegfried Line preparing for the Battle of Hurtgen Forest, the bloodiest, most miserable battle in the history of warfare.

We entered the German town of Roetgen, and then began one of the worst campaigns the company could ever hope to be in. We were attached to the 28th Infantry Division, called the “Bloody Bucket”, and we went into position inside the Hurtgen Forest, in a valley which later on was to be named Purple Heart Valley, as a result of so many casualties suffered there. The forest had been completely mined and booby-trapped, and the engineers did a wonderful job in clearing the territory the infantry was to cover.

The prime mission of the division we were supporting was to go through the entire forest and occupy the town of Schmidt, a well defended town commanding the approach to the series of dams controlling the flood waters which ran into the industrial Ruhr valley. H-hour came, and we proceeded to lay down a rolling barrage of high explosive shells, softening up the enemy defenses. For the first ten minutes, everything was going fine, and the infantry was prepared to go over the hill of the valley we were in, when the enemy let loose with everything he had. Our attack was halted by the tremendous amount of artillery, and it was then that we were aware of how big a job it was going to be to oust him from his dug-in positions and reach our objectives.

Not long after this attack, the weather decided to take up the fight against us, and we began to live through heavy snowfalls, and extreme cold.

The guns remained in the one gun position for a solid month, and somehow the company managed to hold together throughout everything that came up. We saw the 28th Division go, the 8th Division come in, stay for about three weeks and then be relieved by the 78th Division. As usual, when the divisions were relieved, we remained where we were, and took the next assignment with a shrug of the shoulders, for we knew we were there to stay. The 8th Division finally knifed its way out of the forest and instead of this action turning the tide in our favor, it completely exposed us to enemy observation and densely mined flat terrain.

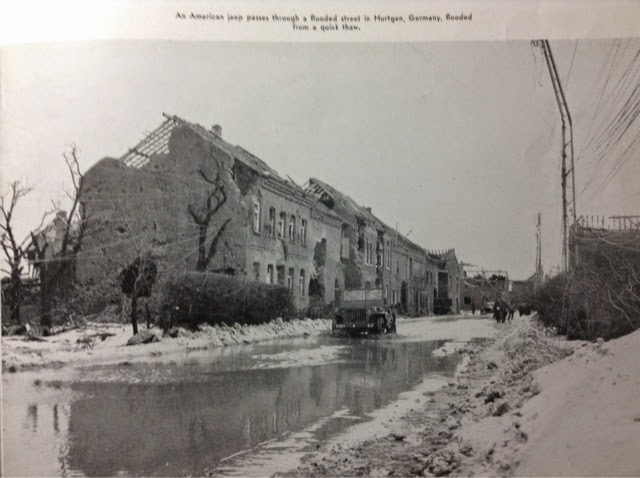

We set up our guns in the town of Hurtgen outside the forest and once more the company was ordered to move out of the town into a small defilade approximately 800 yards from the front line by the infantry commander.

At three o’clock in the morning, the third platoon took off in a column of jeeps and started down the road toward the new position. The leading jeep and the one immediately behind it passed over a certain spot without anything happening, but the third jeep hit what is called a German box mine, and all its occupants were blown into the air and off the road. Immediately after the explosion, the Germans began laying a barrage on the area and once again the men were subjected to a group shelling which took its toll.

This “incident” also displayed the courage of the men in “B” Company, for after working under shell fire on a mined road, they successfully evacuated the wounded men to aid stations and after a quick check, we found that four men had been killed, and thirteen injured. The men killed were Mauck, Olson, Kane, and Homa, boys we had know since basic training, and we took their loss rather hard.

The morale of the company was again on its last legs, for the company commander had completely broken under the terrific strain forced upon him.

With the loss of our company commander, seventeen men out of action, the squads working with one and two men on each gun, and the war still on, drastic steps had to be taken immediately in order to keep the company in the line.

It was about this time that Von Rundstedt launched his historic dash through the American lines and the Battle of the Bulge was on. His strategy was to make thrust toward Luxembourg and after drawing the American forces down into the area of the thrust, he had planned to swing hinge-like to the north to hit the First Army’s salient and cut it by capturing Roetgen, which would put us in an extremely unpleasant position.

However, he ran into a little more than he expected when he began to feel out the “northern flank” and decided that he could more easily keep on going due west and sever the American supply lines which were greatly extended at that time, and by this action isolate the First Army and its troops in Germany.

We were not at all surprised when a re-attachment came down and we were sent out of the Hurtgen Forest down into Belgium in support of the paratroopers of the well known 82nd Airborne Division. They were to hammer at the northern flank of Von Rundstedt’s salient and cut it in two by meeting up with the Third Army which was hammering at the southern flank.

Fighting with these paratroopers was indeed a new experience, for their very actions inspired a “can’t be beaten attitude” and the ease with which they handled all their objectives was something we had not seen since we worked with the 13th Regiment of the 8th Infantry Division at Brest. Each day the guns moved forward, and the gun crews knew that each move forward was taking them that much closer to home.

Major General “Slim Jim” Gavin paid us a visit one day at one of the gun positions and it was easy to see why he had the admiration and respect of every man in his division. Like Eisenhower, General Gavin takes a personal interest in the lowest Joes in the Army and he can make the lowest private feel at ease in spite of the fact that he is face to face with a Major General. He offered helpful and constructive criticsm of the gun position and complimented the company on its fine work.

It wasn’t too long after his visit, that we were given twenty paratroopers to supplement the losses we had sustained in Hurtgen Forest and they came in mighty handy, for we still had the elements opposing us in our operation of the mortars as well as opposition from the enemy. The cold and snow were very severe and the gun positions were of necessity out in the open because the Ardennes Forest is rather dense, and there are very few houses and villages that troops can live in.

We stayed with the 82nd Division until they were relieved by the 75th Infantry Division, a “green” outfit, and again, as usual, we just stayed where we were and started working with them. For a green outfit, they functioned very efficiently and Von Rundstedt’s salient was being reduced day by day. Our fighting took us across the Salm River and into the town of Vielsalm, and by this time, Von Rundstedt’s bulge had all but disappeared, and we began to sweat out a new assignment.

The new assignment was not long in coming and we found ourselves with the 9th Infantry Division battling our way up to the Roer River, about seven miles south of Schmidt, the town which had been taken in almost four months of fighting in the First Army sector. This particular campaign was one of movement, for we were being shunted from one regiment to another and then back again to the first regiment, and each shunt meant moving into the new regimental sector.

After Schmidt had been taken by elements of the 78th Division, plans were laid for the crossing of the Roer River. The crossing of the Roer became headline news. This meant that the Allies now had complete control of the Schwammanuel dams. It was our good fortune to see the main dam and all its huge abutments.

The Germans then began to disintegrate, and we again had a chase on our hands for we made a lightning-like dash from the Roer River to the banks of the Rhine in support of the 2nd Infantry Division. The sight of the Rhine River and the Remagen railroad bridge which had been captured intact by the 9th Armored Division was a wonderful one. We began to realize that organized German resistance was rapidly crumbling and it was just a question of time now until the surrender terms were accepted.

The collapse of the railroad bridge held up progress quite a bit, and once again the engineers showed their prowess by constructing the huge pontoon bridges necessary to insure the flow of men and materials to the fighting front which by this time was on the other side of Hitler’s Autobahn. “B” Company made it possible to cut this vital supply road by screening the advancing infantry with White Phosphorus shells.

Our next assignment saw us containing the Krauts sealed up in the Ruhr Pocket of upwards of 200,000 troops. We remained on the east bank of the Rhine in the vicinity of Seigburg on the Seig River, a position governing the southern escape route which was not closed to the besieged Krauts in the Ruhr Pocket. We remained here for approximately three weeks when a new assignment with the 104th Division came through.

After a long motor march we found ourselves in another rather shaky position. We were on the tip of the finger that was trying to close up the Ruhr pocket making a junciton with the Canadians who were coming down from the north. There was very little action during this period, and after a couple of weeks in this region, we received another assignment which was to be the most interesting one we ever had.

We were attached to the 9th Armored Division that had established the first bridgehead across the Rhine, joining them at Mulhause. Their objectives were to be a junction with the Russian Army, if possible, and to secure all the ground west of the Elbe River, which runs approximately north and south through the center of Germany. Our spot on the river would place us southeast of Berlin, and naturally we were anxious to get rolling, for the end was at last in sight. We started out with Combat Command B clearing all the towns which lay in our path, and it was practically a non-stop flight across the flat land which characterizes the center of Germany.

Even on this last leg of the war, the company was to have another “incident” and it came about very unexpectedly. We were in the armored column in the vicinity of Bilzingsleben and parked on the road leading into the town. The time was about five o’clock in the afternoon and the brilliant sun was to our backs and we were feeling rather good, when, from out of the sun came four ME-109s with a perfect target of a long line of vehicles. They came in unannounced and undisturbed, for the anti-aircraft units were caught napping and they offered no resistance to the planes until after they were well started on their strafing and bombing mission.

For some reason or other the planes concentrated on “B” Company’s string of vehicles and every bomb that hit landed on the road where we were parked. It was really terrifying, for the sound of a bomb screaming down, is a sound never to be forgotten. Once again we added up the damage done, and we found that good old Hinchy had been killed instantly when a bomb struck the truck under which he had sought cover. Seven other men had been seriously wounded and after they were taken care of, we again took off with the grim reminder that the war was still very much on, regardless of what the home papers might be saying.

Three days later found us east of Leipzig, in the small town of Wolpen where we were to fire our mortars for the last time. After shelling Eilenburg for several days, we were once more relieved for another assignment. A long motor march over the Reichsautobahn and we found ourselves in Southern Germany, acting as police troops.

Here we went to work cleaning the woods of Wehrmacht stragglers who had banded together constituting a serious threat to our over-extended supply lines. This was something new for Baker Company, but it proved its adaptability by overrunning a Wehrmacht bivouac area, thus greatly lessening guerrilla activities in this sector.

We seemed destined never to stay very long in any one place. Once again it was that familiar cry, “March Order”, that sent us on our way to Hirschau.

Thus it was the V-E day found us in Hirschau and wondering what would happen next. We had been in combat 300 days; we had supported 28 different divisions, 8 corps, and 3 armies. We all hoped to be in the Army of Occupation, but deep within us we knew that we were destined for the Pacific.

From Hirschau we moved in Battalion convoy to a town in Czechoslovakia called Bischofteinitz, and after staying there for about three weeks, we were finally alerted for a long trip through Germany and into France where we were told we would embark for home and 30 day leaves in the states. You can imagine what a thrill it was to think that after 15 months overseas we were at last going home to see our loved ones. Thoughts of the Pacific were thrust aside, for the combat man learns to live for today and let tomorrow take care of itself.

Our staging area was Camp Lucky Strike, that large tent city located near Le Havre. The convoy from Bischofteinitz to Le Havre was long and wearisome, but our spirits were high with thoughts of home—nothing could daunt us.

We stayed in Camp Lucky Strike for two weeks, but it seemed at least four times that long, so eager were we to get started toward home. At long last, that day of departure arrived. There never was or will be a happier band of men than “B” Company on that occasion, although the weather did not share our enthusiasm. A driving rain soaked everyone to the skin; but even that failed to dampen our spirits. With light hearts we boarded the S.S. Sea Pike, homeward bound.

A calm voyage under sunny skies, eight carefree days and we docked at New York. Home at last! From New York we traveled by train to Camp Kilmer, where we were separated into groups according to the location of the re-deployment centers nearest our homes. Then came those glorious furloughs, thirty days which ended all too soon.

While we were enjoying this respite from war, our Pacific Forces were carrying total destruction to the shores of Japan. The atomic bomb forced the Japanese government to sue for peace and thus it was that while we were returning to our new station, Camp Campbell, Kentucky, the war officially came to an end.

This great news brought forth a tangled mixture of emotions—relief, happiness, and sadness. We were relieved to know that there would be no more combat for us; we were happy with the thought that now we could go home and stay; but it was with sadness that we thought of our friends who were not with us to celebrate this great day.

Now the saga of “B” Company is coming to an end. With each departure of a high point veteran goes a little bit of that glorious past which has marked this organization’s history. Soon there will be nothing left but these words to commemorate the brilliant traditions of Baker Company, 86th Chemical Mortar Battalion.

Excerpt from The Battle History